An overview of ESG risks in the financial sector

Perspectives / An Overview of ESG regulation for EU based financial institutions

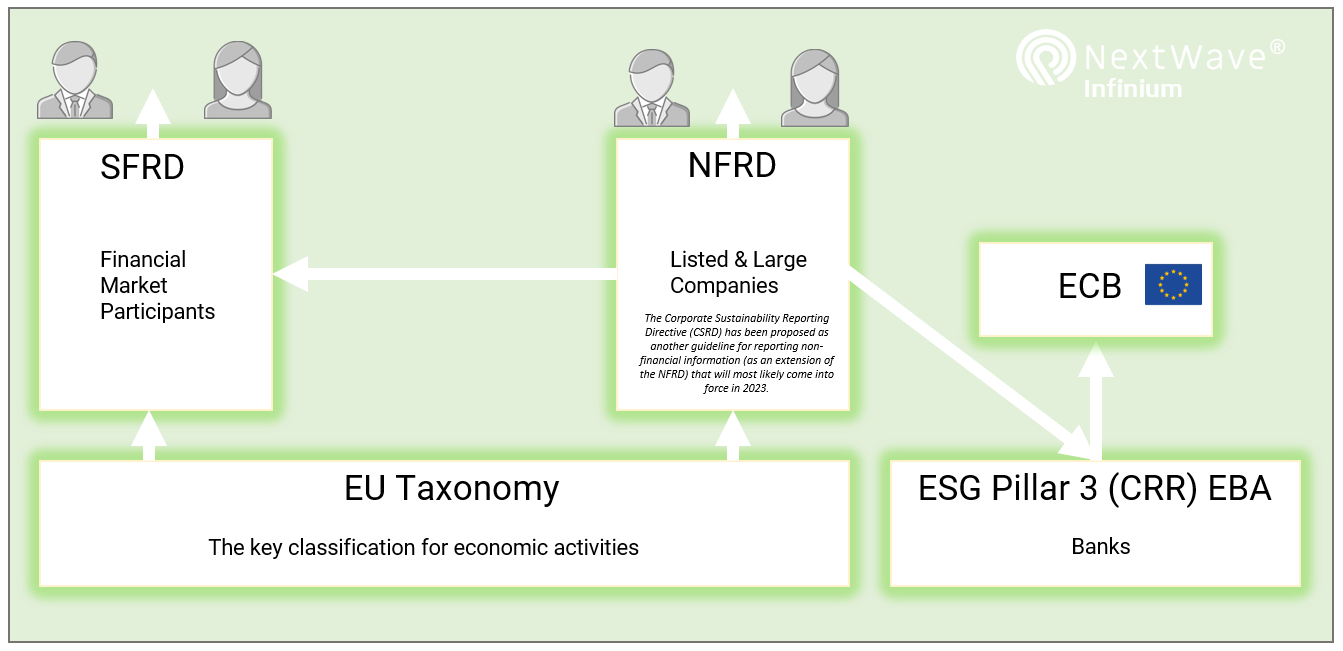

In line with the European Commission’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan, the EU has taken a number of measures to ensure that the financial sector plays a significant part in achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal . Disclosure of information on ESG risks in the financial sector is central to achieving this goal, and therefore regulation has been developed to ensure transparency and discipline in financial markets. Here we provide an overview of the most important current regulation concerning ESG disclosure in Europe for ECB regulated banks and listed and large companies.

Regulations have binding legal force throughout every Member State are binding and to be applied on a set date in all the Member States. Directives lay down certain results that must be achieved but each Member State is free to decide how to transpose directives into national laws.

The NFRD: The non-financial reporting directive

Came Into force: 2018

Applies To: listed companies (also banks, insurance companies, public interest entities)

.jpg?width=317&height=211&name=pollution-environmental-2021-08-30-16-33-45-utc-2048x1365%20(1).jpg) The NFRD (Directive 2014/95/EU) is a directive that requires listed companies to publish regular reports on the social and environmental impacts of their activities.[1] It lays down the rules on disclosure of non-financial information by certain companies.

The NFRD (Directive 2014/95/EU) is a directive that requires listed companies to publish regular reports on the social and environmental impacts of their activities.[1] It lays down the rules on disclosure of non-financial information by certain companies.

These disclosure requirements for large companies should help investors, civil society organizations, consumers, policy makers and other stakeholders to evaluate the non-financial performance and ESG practices of these companies. [2]

The CSRD (The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive)

Comes Into force: 2023

Applies To: listed companies (also banks, insurance companies, public interest entities) & large private companies

In April 2021, the CSRD was adopted by the European Commission. The CSRD amends the reporting requirements of the NFRD. The CSRD requires more detailed disclosure than the NFRD and requires that this information is also audited. [1]

A crucial point in the CSRD, is that the scope of companies that had to report under the NFRD, has been broadened. With the CSRD, not only listed (and other) companies should report on their ESG practices, but also when a company satisfies 2 of 3 specific conditions. These are that the organisation has: [2]

- more than 250 employees,

- more than EUR 40 million in annual revenue,

- more than EUR 20 million on the balance sheet.

With this amendment, it no longer matters if the company is listed or not (as was the case in the NFRD). This amendment has increased the entities in scope from~11,600 under the NFRD to ~49,000 in the CSRD. [3] With the introduction of the CSRD, a new principle was also introduced: the double materiality principle. This means that the large & listed companies have to report not only on how their operations impact the environment and people, but also as to how sustainability issues affect their business.[4] In many ways this echoes the approach from the TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures) recommendations published in 2017 which emphasize the impact on a firm’s strategy as much as the actual disclosures themselves. All reporting under CSRD has to align with the EU Taxonomy regulation.

The SFDR (The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation)

Came Into force: March 2021

Applies To: Financial market participants and financial advisers

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) lays down an ESG disclosure obligation for financial market participants and financial advisers towards their end-investors. [1] In this case, examples of financial market participants include asset managers, pension funds and insurers. The SFDR obliges all entities offering financial products where they manage clients money and financial advisers to disclose adverse ESG impact on both entity level (the ESG impact their own practices have), as well as on product level (the ESG impact that their financial products have).

The SFDR requires financial market players to disclose whether a financial product should be classified as a:[2]

- Article 6 product – a product with no sustainability objective

- Article 8 product – promoting environmental or sustainable characteristics (‘light green’)

- Article 9 product – sustainable investment as its objective (‘dark green’)

- Additionally, financial market players should disclose of principal adverse impacts (PAIs) on both entity and product level. There are 50 PAI sustainability indicators (some mandatory and some voluntary) covering a range of ESG issues including greenhouse gas emissions, human rights and waste management.[3]

The implementation of the SFDR, just as the implementation of the NFRD/CSRD, is influenced by the definitions in the EU Taxonomy.

The SFDR itself can be referred to as Level 1 legislation. Derived from Regulations are implementation decisions like regulatory technical standards (RTS), referred to as Level 2 legislations. Level 1 of the SFDR, that is already in force and asks financial market players to sort their products into article 6, 8, and 9 products. Level 2 of the SFDR (delayed until 2023), requires managers to provide proof that supports the classification via PAI disclosures.

Citing ESG policies is not enough to be classified as an Article 8 product: An interesting development is that there are many funds that have declared themselves as Article 8 funds, even though they have not assessed each of the holdings in their fund, according to the PAI’s.

The EU taxonomy

Came Into force: July 2020

Applies To: listed or large companies under CSRD (stating % of activities aligned with taxonomy), financial market players under SFDR (stating what products are labelled as under the taxonomy)

The EU taxonomy is a classification system, establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities.[4] Businesses of any size, including small companies, can use the EU Taxonomy to explain to investors or stakeholders in general whether they carry out or plan to carry out Taxonomy-aligned green activities.[5] The rationale behind the EU Taxonomy is to make it easier for investors to assess whether an investment is sustainable, prevent greenwashing, and to stimulate companies to assess their activities against common definitions and standards. Overall, it is intended to improve confidence on ESG disclosures.

The EU Taxonomy lays out 6 environmental objectives:

- climate change mitigation,

- climate change adaptation,

- sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources,

- transition to a circular economy,

- pollution prevention and control, and

- protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

The EU Taxonomy also sets out 4 conditions that an economic activity has to meet to be recognised as Taxonomy-aligned:

- making a substantial contribution to at least one environmental objective;

- doing no significant harm to any other environmental objective;

- complying with minimum social safeguards;

- complying with the technical screening criteria.

Together with the CSRD, the EU Taxonomy ensures that companies falling under the scope of the CSRD disclose the environmental performance information of the company, as well as information about a company’s Taxonomy- aligned economic activities. The SFDR requirements are linked with those under the EU Taxonomy, by including ‘environmentally sustainable economic activities’ as defined by the Taxonomy Regulation in the definition of ‘sustainable investments’ in the SFDR.

The banking sector

In addition to regulation that applies to listed or large companies and for financial market participants and advisers, there are also ESG disclosure regulations in place specifically for banks. In the EU, the European Banking Authority (EBA) is mandated to set binding standards that are endorsed by the European Commission, have direct application, and need not be implemented in national legislation and regulations. [6] The EBA also has the mandate to ensure that ESG risks can be incorporated into the three pillars of prudential supervision for the banking sector.

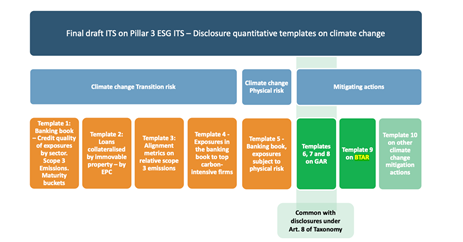

On 24 January 2022, the EBA published its final draft implementing technical standards (ITS) on Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks, in accordance with article 449a of the Capital Requirements regulation. These ITS put forward comparable and mandatory disclosures to show how climate change may exacerbate other risks within institutions’balance sheets, how institutions are mitigating those risks, and their ratios, including the GAR (Green Asset Ratio), on exposures financing taxonomy-aligned activities, such as those consistent with the Paris agreement goals.[7] The EBA has, when developing their technical standards, built on the guidelines and recommendations of several other important, influential bodies dealing with banking regulation, such as the European Commission, Financial Stability Board Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (FSB-TCFD), and the before-mentioned EU Taxonomy.[8] Not surprisingly, the EBA has aligned the reporting on KPI’s to the EU taxonomy, so data and timelines can be matched to the NFDR/CSRD taxonomy alignment disclosure requirements.

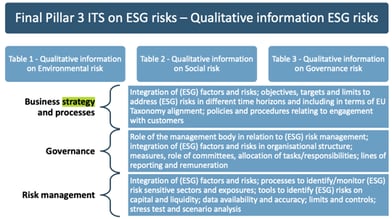

The mandatory Pillar 3 ESG disclosures are laid down in the Capital Requirements regulation (CRR) article 499a and include the following:[9]

Quantitative disclosures on climate change transition risks, including the following templates:

-

- Credit quality of exposures by sector, emissions and residual maturity

- Loans collateralised by immovable property – energy efficiency of the collateral

- Alignment metrics for the banking book on relative scope 3 emissions

Exposures in the banking book to the top 20 carbon-intensive firms in the world.

Quantitative disclosures on climate change physical risk, including the following templates:

- Banking book: exposures subject to physical risk

- Quantitative information on mitigation actions

- Qualitative disclosures, including qualitative information on environmental, social and governance risks, relating to the business strategy and processes, governance, and risk management.

The Green Asset Ratio (GAR) is a ratio that shows which part of the banks banking book is aligned with the EU Taxonomy, focusing on companies that fall under the scope of the EU Taxonomy (so in this case the NFRD). The disadvantage of the GAR calculation is that a lot of companies do not fall under the NFRD and are not included in this ratio. Of course, when the CSRD comes into force, the scope of the NFRD will be extended to more companies but will still exclude many smaller companies.

This is where the BTAR ratio comes in, which indicates what part of the banking book, now including counterparties not subject to the NFRD, is aligned with the EU Taxonomy.

The BTAR ratio will therefore allow for a truer reflection of the taxonomy alignment of banks. The BTAR will also address some important concerns about the limited scope of the GAR, such as the potential negative effects on credit flows or the lack of incentive for banks to support the transition process of companies outside the scope of the NRFD.[10]

Institutions will have to start disclosing on disclosure requirements laid down in 499a CRR from June 2022 onwards, with some aspects requiring disclosure as of 2023 and 2024. The European Central Bank (ECB) will in turn ensure that banks follow the rules set forth by the EBA.

Source: Both diagrams were published by the EBA and can be found on the EBA web-site https://www.eba.europa.eu/

Implementation challenges for EU regulated banks

There are certain challenges that banks will face with the EBA’s implementation of Pillar 3 disclosures.

Firstly, the quantitative disclosures required by the EBA’s technical standards require banks to report on their counterparties’ scope 1, 2 and 3 greenhouse gas emissions. Common difficulties in reporting on scope 3 GHG emissions include reliance on supply chain partners, data gaps and poor data quality.[11]

A second challenge arises in the requirement for banks to report on their exposure to physical climate risks, such as floodings, droughts, and other extreme weather events. To be able to report on this, specialised databases will need to be consulted to compile a detailed understanding of these exposures, and banks will further need to compile a narrative that explains the methodologies they used. [12]

A third problem arises when calculating the BTAR; the ratio that focuses on counterparties that do not fall under the scope of the NFDR, such as SME’s and non-European counterparties. While this expanded scope is a welcome initiative, since it will better reflect a banks’ true alignment with the Taxonomy, it will be much more difficult for banks to gather data from these companies.

This is because the NFDR requires companies to report on ESG data in a (more or less) standardised and complete manner, making it easier for banks to use this data. However, when banks need to use data from companies that do not fall under the NFRD (needed for the calculation of the BTAR), the gathering and assessing of ESG data will most likely be much more difficult. To fill these data gaps, it seems unavoidable that banks will have to use proxies and estimations, thus distorting the true picture.

Another challenge relates to using external ESG data sources to report on ESG requirements. In some cases, it will not be sufficient to use only data that is available within the bank or within the client base. As a result, banks will have to resort to use numerous external data sources to make up for the lack of completeness in their data. The issue with this is that banks often do not have insight in the methodologies used by these external data suppliers when creating this data.

As such it will be difficult for banks to verify the validity of the data and the outcomes, and in turn will also make it more difficult for banks to explain and defend their results to their regulators.

References

[1] Communication from the Commission – Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth, COM(2018)097 final.

[4] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0189

[6] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0189

[8] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_21_1806

[11] https://www.greenstoneplus.com/blog/the-sustainable-finance-disclosure-regulation-sfdr

[15] https://www.eba.europa.eu/eba-publishes-binding-standards-pillar-3-disclosures-esg-risks

[19] https://blog.smartersorting.com/scope-3-reporting

[20] https://zanders.eu/en/latest-insights/ebas-binding-standards-on-pillar-3-disclosures-on-esg-risks/

Interested in digital acceleration?

Subscribe to NextWave for occasional email updates on the latest technology, acceleration approaches, news and NextWave events. You can unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

Subscribe for our latest updates

Tags:

Sustainable Finance

May 18, 2022